“Dude. Have any of you guys tried to buy a new mouse recently? I’ve been doing some searching, but I’m going into analysis paralysis here.”

“I haven’t. I need to, but I have been stressfully avoiding it. For probably at least a year or so.”

“The fuck do you need a mouse for? I thought you controlled everything using a flight stick?”

“Ha. That would be hilarious.”

“We should all pitch in to get him a flight stick– just to play this…. just to see him try to use it.”

“I bet we’d be doing a lot better if he had a flight stick…..”

“… Honestly, I probably wouldn’t even have a kill yet if I was playing with a flight stick….”

“Dude, you wouldn’t even be able to figure out how to launch the game with one of those. You’d be like a 5th grader playing with crayons for the first time.”

“Ummm…. I don’t know about you, but I’m pretty sure I played with crayons before the 5th grade…”

“Ahhhhhhahah!!! I love it. Zero hesitation.”

“…He’s probably right though.”

“About the 5th grade or the flight stick?”

“Fuck you.”

“I know how to use a real flight stick in a goddamn aer-O plane, and I guarantee you, I wouldn’t be able to get a kill with a flight stick in this game.”

“… You guys buy me a flight stick and I’m going to quit this shit and go play Elite: Dangerous.”

—

Buying a computer mouse today is extremely difficult, especially for someone who knows what they are doing. There is an absurd amount of technical language that one has to filter through– which is made all the worse by a parade of acronyms concerning mouse-like abilities…. It is very easy to get lost, especially once you start making basic decisions concerning whether you want an optical mouse or a laser mouse– wireless, or corded.

For someone who knows precisely what they are looking for, and who is intimately aware of how it will effect their use of such a tool, the process might as well be an exercise in futility. For people who use computers a lot– and not just for working– mice are intimidating devices despite their innocuous slight physical appearances. For these people, mice are intimidating because they know exactly how the device will effect what they do with it.

Up until very recently (as in the last year), most of the previous academic focus on videogames has come from fields that are largely disinterested in what people are doing while they play. This blog post, quite literally, would not have been written by an academic even 10 years ago. Part of this is attributable to the additive properties and possibilities of language– but it’s also largely due to what and how academics find themselves concerned with things. Usually we are more interested in building a type of knowledge about videogames that is fundamentally detached from videogames and the people who play them. This type of research (featured occasionally on your evening news) is easily identified by people who play, because it usually involves testing of some kind, a subject population (people with a potential for violence), and a heinously dated videogame. Regarding this last point– researchers usually try to explain this away in advance of any actual conversation by stating that modern games are immensely difficult to decode. Of course they are correct in saying this– from the perspective of people who don’t play them.

—

Bourdieu, in talking about what he refers to as the “logic of practice”, makes reference to Mauss’s famous ethnographic work when he examines the reciprocal act of giving a gift. Mauss’s example is brilliant– but we are going to translate it here into something that makes more sense to us…..

Much of the negative criticism concerning videogames has been directed at what might be called their propensity for instilling violent behavior. “What is at stake is the indoctrination and corruption of our youth!”– if you want to use language that is a little more ham-fisted…. First Person Shooters in particular make for easy targets for these types of criticisms. Part of what is problematic with this form of reading however, is that it is too theoretical and is often radically disinterested in what is entailed by actually playing.

Back to gifts: whatever the circumstances, most people give gifts to other people at some point throughout the year. Giving a gift carries with it all sorts of meanings. Does one expect a gift in return? Is one giving a gift in reciprocation of something else, another gift received? If one is reciprocating a gift, how long after receiving a gift should one give a gift in return? If one was late in reciprocating, is one in trouble when they actually give the gift? Does one choose to call something a gift, that is not a gift? All of these things matter regardless of the type of gift that is given.

Instead of getting caught up in the meanings of the gift, as Bourdieu emphasizes, what we should look at is the act of giving a gift itself– where a gift is composed of a whole nexus of thoughts, expectations, predictions and calculations. Things get interesting when we realize that this type of thinking is generalizable to lots of different settings.

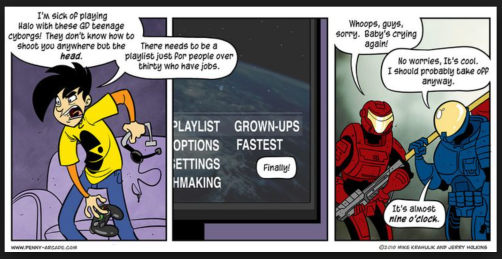

Back to videogames: much like in Fencing, through the course of a first person shooter match exchanges of gifts (attacks, ripostes, logics and counter-logics, predicted defensive maneuvers….) happen at massively accelerated speeds. In order to “succeed” in a FPS match, players need to able to calculate distances to each other, predict complex physics involving weapon charge up times, the state of the target (i.e. airborne vs. grounded), your own state (airborne, grounded, sprinting), target groupings, map positions, weapon reload speeds, and their teammates own proximity and communications…. all in order help manage damage going in multiple directions. “Success” here, is also a word that is up for debate. Many people just like playing because it lets them goof off with their friends. Frequently we don’t care who won the match, unless we are trying to play at a very competitive level for some kind of reward. Most of the time, play is its own reward.

In other words, playing a FPS game with your friends isn’t a murder simulator. Rather its an education in practical dialectics during which you get to swear at your friends and talk about stuff that’s going on in your life outside of the videogame. It’s about play.

Someone might make the argument that this all sounds a lot like Orson Scott Card’s “Battle School” in Ender’s Game. Such a reading would be interesting, and would probably result it some curious and important arguments about mythology and ideology (a la Roland Barthes)– but such a criticism would also need to account for the fact that nobody here playing the game is dying or is killing anyone else while they are playing. Granted we all might be being trained to fight or to think in a certain way– but according to Bourdieu, Mauss, Levi-Strauss, or virtually any theorist, these are ways of learning that we are going to be picking up regardless of videogames. At risk of sounding like an apologist, perhaps we should be looking at playing more, and less at what the gift “means.”

In other words, what actually happens when people play?

—

It takes some imagination, but one can think how buying a mouse– or a competition grade controller of any kind– gets complicated very quickly. (This is to say nothing of a flight stick.) Professional players, when they do this, cannot think just about the mouse. They must also consider how the mouse will effect what they do in the game. On a controller or a mouse, pressing a button takes time. Certain types of button combinations or trigger pulls get used frequently. Being able to do these things faster and smoother means having to think about them differently– which changes the way we play with each other. Being able to jump in a FPS game, while continuing to aim confers changes certain types of thoughts about how someone might move around a game– these are differences which are more noticeable if previously you were only able to jump (and not aim) due to limitations of the hardware or software.

The catch comes, when people who don’t play start to realize that they do this as well when they think about purchasing a mouse. They think about what type of surface they want to use the mouse on. They might think about whether they want a wireless or corded mouse. They think about what color of a mouse they want, and if it will match their computer. The don’t frequently think about which mouse they want to use (many players own at least three mice). They don’t think about mouse durability. Most don’t think about if the mouse is accurate enough for their needs. Most don’t even think about the position of the cord coming out the front of the mouse, and if it will interfere with how they move the mouse around next to their computer.

Videogames aren’t inherently bad or good as a category of entertainment. There of course are “bad” and “good” games according to games journalism. But this type of journalism is concerned with a different level of discourse which is geared towards telling people who already play whether they will like a specific game or not. Calling FPS games murder simulators is sort of like bumper sticker politics. Saying something like: “Ayn Rand Was Right” is a crude statement that presumes everyone is in consensus with what you think you are saying in the first place. Okay…… well, presuming we are even in agreement that she was right about anything, or that we think she is talking about the same things, what was she right about?

In addition to talking about what things mean (which changes constantly), lets also talk about practice. Lets talk about mice and what it means to use them. Lets actually talk about games and the dialectics that take place in them.

Lets talk about objects and what it means to think with them.

—